Lieutenant Commander Alan Tyler. Age 92

A navy cadet at 13, Alan Tyler served throughout the war, remaining in service until the 1960’s. Alan participated in extraordinary events including the sinking of both the Scharnhorst and the Tirpitz, escorting Churchill, the liberation of Singapore, the founding of the State of Israel and Britain’s first atomic tests.

Alan was interviewed at his home in Surbiton on 15th May 2015

Alan can you tell me a little about your background. My name is Alan Tyler, I was born in Willesden in 1924, my parents were born in London area. I went to a pre-prep school in Willesden then I went to a boarding school at age eight at Uckfield in Sussex, from there when I was 13 in 1938 I went to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth as a regular Royal Naval officer cadet.

What drew you to the navy as a cadet. Partly at the time we had the biggest navy in the world and you know there was an awful lot about Nelson the navy and the high seas and I suppose I was particularly attracted to it. There were several others at school who also went onto Dartmouth.

I was 15 and a cadet at the college when war broke out. We completed our training at Dartmouth at 17 and then went to sea with the rank of Midshipman, which is a sub-officer as it were. I was appointed to a ship in Alexandria in Egypt and as the Mediterranean was closed pretty well to traffic we went right round the Cape in a merchant ship and ended up a couple of months later at Suez, took a train to Alexandria and arrived the day after the Italians had put a couple of midget submarines into Alexandria harbour and blown up our two battleships the Queen Elizabeth and the Valiant. They didn’t actually blow them completely up but the blew the bottom out of them and so that was carefully disguised from the enemy and we carried on normally.

I joined a cruiser called the Ajax and for about a month we were sitting in Alexandria harbour and occasionally running convoys to Tobruk, which was cut off by the German advance, it was a pocket of allied resistance.

We then went down to Suez as the guard ship there from where Ajax was sent back to England and us midshipmen were decanted and sent to destroyers, I joined a destroyer called the Hasty, again in Alexandria and we ran convoys to Tobruk to Malta to Cyprus to change the garrison. Those were about the only three places we held at the time. In March we escorted a convoy going to Malta and the Italian fleet came out to attack us, we had three light cruisers and a few destroyers escorting the convoy, the Italians had a battleship and heavy cruisers and the like. The destroyers laid smoke screens and went through to attack the Italians and the Italians turned away because they didn’t want to risk their ships, they weren’t anxious to sacrifice their lives for their German allies.

Were you stationed in the Mediterranean throughout the war. Good heavens no. After a couple of months they said you’ve finished your destroyer time and we were transferred down to join the eastern fleet which was based at Mombasa because we’d withdrawn from the far east with the Japanese threat. The battleship I was to join had moved down to Durban and we joined it there, where she was refitting being modernised because she’d been at Jutland, she was pretty elderly ship by then so we had a few months in Durban where we did a lot of naval training.

We were then sent back to England in 1943 for our sub Lieutenants courses, took the summer of 1943 going to the various schools, gunnery school, navigation school, torpedo school etc. and then I was sent to join a cruiser called the Norfolk in the home fleet at Scapa Flow where I was the sub lieutenant in charge of the gun room. All the bigger ships had gun rooms for midshipmen, whereas the ward room was for all the other officers.

The first thing we did was go out to escort Churchill back from one of the Quebec conferences we met him in mid Atlantic, he was in the Queen Mary and we escorted him back. That was the nearest I got to America in my entire naval career. Then we escorted convoys to Russia, up to Iceland and escorting them to near Murmansk where they were handed over to the Russians.

In December 1943, for the first time, we were allowed into Murmansk and were allowed ashore, there was nothing much to see. It was a wooden town built in the first world war, the Germans had firebombed it, there was virtually nothing standing, there was nothing to do so we just walked around one afternoon, we could have free copies of Pravda or Isvestia Which we couldn’t read, we bought stamps in the local post office in exchange for cigarettes.

We then took the next convoy going back from Russia to England. On Christmas day we got warning that the Scharnhorst, the German battleship in northern waters, was coming out to attack the convoy, so we got between the convoy and the mainland and on boxing day morning we sighted her and opened fire. There were three of us cruisers, and we were the only one with heavy guns, we had eight inch guns, so we opened fire first and by great good fortune we hit her one major radar set, so in the dark of the winter days in the Arctic they couldn’t see anything.

The Duke of York caught up with her in the evening by which time she was already damaged and they pumped their 15 inch shells into her, she was very strongly built. Eventually she was sunk by destroyers going in with torpedoes and torpedoing her a lot of people obviously been killed in the fighting but in those waters if you were in the sea for half an hour you were lucky to survive and I think there were 34 survivors out of 2000 all together. Of course the merchant ships that suffered in all the convoys, they were the bravest ones, they didn’t have guns like us.

We also had the misfortune that we were the only one using ordinary cordite, which produced a flash as opposed to the lighter cruisers that had the modern cordite which didn’t, so the Scharnhorst aimed at us and they put two 11 inch shells right through us. Fortunately our armour was sufficiently light that it didn’t set off the shells otherwise we wouldn’t have been here to tell the tale. It didn’t actually do us any harm because it was above the water level so we continued with the convoy back to England where the ship was sent into dockyard to repair.

We transferred to her sister ship the Devonshire which was just completing a refit so the whole ships company moved from one ship to the other and then we went back to Scapa Flow and spent the summer escorting aircraft carriers going over to Norway to attack the Tirpitz the last remaining German battleship and any convoys running up and down the coast.

Was there a particularly low point for you during the war. I don’t think there was a low point. We were very young and naïve we didn’t get particularly depressed, and of course the worst of the war was over by the time I went to sea. We’d had the battle of Britain. America came into the war just as I was going round Africa on my way to join the Mediterranean fleet so I reckoned we’d be OK and of course we had the Russians fighting like mad.

Towards the end of the year we came down for local leave and I went to the Admiralty and said, You know I’m getting a bit bored with this can I get something a bit more interesting? And they said well you can’t do that sort of thing but in fact we’ve put you down to go and join a frigate. So I went a joined a frigate called the Blackmore, which was refitting in Chatham, and early in 1945 we finished our repairs and we escorted a few convoys running over to the Shelt backing up the army, which then hadn’t yet crossed the Rhine.

After a couple of months of that they said were going to send you out to the Far East. We were the first of the light Hunt class frigates to go out to the far east because we had only limited range and speed. I was the navigating officer of this frigate and when we got to Aden, they said sail to Colombo and I worked it out on the back of an envelope and said we’re going to run out of fuel before we get there, terribly sorry we cant get to Colombo, so they said do you think you can get to Bombay? I said yes we can make Bombay, so we got to Bombay spending four days at sea from Aden to Bombay just using star sights and sun sights like they’d done in Nelsons time. I knew we were going to hit India but I was very pleasantly surprised when Bombay came up on the horizon and we arrived funnily enough the day before Passover.

I went to the Seder service at the army welfare in Bombay, I’d been to one funnily enough at Famagusta, Cyprus when I was in the Mediterranean, that was the first time I discovered there were Jews in Palestine because there was a lot of the Palestine Corps there.

Then we carried on round to Trincomalee, the naval base on the eastern side of Ceylon, where we were based for a month or two and then it came to the invasion of Burma. We were sent up with RAF meteorologists on board to let off meteorological balloons to forecast the weather in Rangoon for the British assault, we then went back to the Burma coast and embarked a lot of people who wanted to come back to Ceylon so we spent VE Day somewhere between Burma and Ceylon, we got them to Trincomalee the next morning to celebrate.

We then sat in Trincomalee most of the summer escorting aircraft carriers going over to attack the Japanese in Sumatra and Malaya.

Finally the first atom bombs were dropped the end of the war came on 15th August then early in September the fleet went through to do the liberation of Malaya and Singapore, a big fleet, British battleship and a French battleship that was going on up to Saigon. We practiced the landing because we going to attack Kuala-Lumpur. We sent in all the landing craft to Port Swettenham, about half of which ran aground on the sandbanks, of course they’d have been sitting targets for the Japanese. Fortunately that didn’t arise.

We were detached from that group to go onto Singapore where we led the British fleet in. They reversed the line and we came from tail end Charlie right up past all the destroyers, cruisers, aircraft, carriers and battleships right to the front, nobody told us at the time but it was just in case the Japanese minefields weren’t where the Japanese said they were, we were the ones to find out, but we got safely into Singapore, anchored there and there was a ceremonial surrender to Admiral Mountbatten as the Far East Commander. Then we could go ashore and the whole Padang, the big grass square in the centre of Singapore was covered with surrendered Japanese soldiers the whole thing was Khaki on the green, squatting down there.

All the street were decorated with Japanese inflation money which was completely worthless they didn’t even have control numbers on the notes and all the Chinese shop keepers who had hidden away their Straits Dollars before the war, brought them out and started trading straight away.

I went away to rescue, to help a couple of my fathers friends one of whom was a rubber planter in Malaya but he was also a doctor and had been in the RAMC in the first world war, so we were able to help him with clothes and money and he went off back to England.

I also went to see the Synagogue, which had been used as an ammunition depot by the Japanese who were being forced to de-ammunition it so that it could be put back into service. All the Jews were treated as Europeans funnily enough and as enemies and therefore interned and they weren’t discriminated against as Jews, they all survived although they were pretty hungry like most of the refuges. One family I knew was clever enough to unwrap bars of soap, wrapped notes inside and then sealed them up again inside their wrappings so they had money to buy food, a lot of people got up to tricks like that. On the whole the Chinese were very supportive and tried to get food to them, Singapore was mostly a Chinese city.

After the war where did your career take you. We hung around the far east for a month and then they said well we’re going to send you home so off we went back through the Mediterranean and got back to Plymouth in December 1945 and they said we’re going to pay off your ship, we don’t need it any more, you’re due for your end of war leave and you can have it for the month of February. That wasn’t the best of times, it was freezing cold and of course there was very little gas or electricity so I spent my end of war leave mostly crouched over a gas fire.

Then they said go and do some more courses, you’re now a lieutenant, so I did some more courses and went off in June 1946 to the Mediterranean to Malta to join a new destroyer called the Chevron, she was one of a flotilla of eight of the CH class destroyers. This was just after the King David hotel and the captain came down to the wardroom one day and said I suppose you’re prepared to come to Palestine to do the patrol, I said of course, because we weren’t very pleased with the IZL (Irgun) and the others.

Funnily enough in 1939 when the illegal immigration began, when the government said you can have 1500 a month allowed, they’d started coming in the summer of 1939 and the Palestine police couldn’t cope and called in the Navy then to do a Palestine patrol and turn them away and this was revived at the end of 1945.

Again the refugees started coming in from Europe and they normally had one destroyer on the three mile limit and another one about five miles further out at sea to try and divert these ships. The government had information of course on all the European ports and knew when the ships were sailing and the RAF was also flying flights and we almost always knew when illegal ship was coming in. We called them Illegals, and we just stood by, in fact at that time we just stood by other which destroyers were doing the boarding. So that particular first month we saw one or two ships coming into Palestine with the loads of refugees on deck but we didn’t actually take any physical part.

And then we went off to do other duties in the Mediterranean we went to Greece we went to Cyprus and we went to Italy but this was the height of austerity in England just after the war 1946, they couldn’t afford the hard currency for us to go to France, we couldn’t go to Spain, it was Fascist and they didn’t approve of it so we were stuck in the Eastern Mediterranean almost the entire time.

The end of 1946 we were on patrol off Haifa and one of the refugee ships ran aground in the Dodecanese, those are little islands which the Italians had pinched from the Turks before the first world war, they were going back to Greece but they hadn’t yet, they were still under British control. On a tiny islands called Syrna with a population of one family, this ship called the Athina ran aground with about 750 refugees and they managed to get all but four ashore which was fortunate. They got a radio ashore and they were able to call up and ask for help. So we were detached from the Palestine patrol to go out to Serena with the minesweeper Providence, to try and evacuate all these people, which we eventually did. It was quite rough but we sent the ships boats in and I was in charge of that on shore getting all these women and children and refugees into the boats. Not too many so they didn’t sink or anything, back to the ship where the children were hoisted up in potato sacks to the horror of their mothers but the most sensible thing to do while the others had to scramble up ladders.

Along with the minesweeper we got the whole 750 off and we were then sent to Crete where they were transferred to a landing craft that took them off to Cyprus to be interned. They were very grateful for being rescued and there was no trouble aboard us but there was a bit of trouble on the landing craft when they realised they were being taken back to Cyprus and not Palestine. That was one of the very few immigrant ships, which actually didn’t get safely through to Palestine. Considering how old and decrepit they were. They were the only things that the Palyam the sea side of the Palmach were able to get hold of and run.

In March we actually did a couple of intercepts of ships. The first one was straightforward we put a few men with pick axe handles, they had got Sten guns but they didn’t have to use them, to take charge of the ship and bring it into Haifa where they were transferred to the transport ships which took them over to Cyprus. The internment camps in Palestine were already full and they said we’ll send them to Cyprus, the idea being that it would discourage them, which it didn’t of course.

The second ship we intercepted was a rather smart yacht called the Abril, which was the only ship, which the IZL ever actually sent refugees in. The captain had scarpered with money when the ship left Marseilles so the crew had brought it over to Palestine and didn’t offer any resistance, they were only too happy to get the ship turned over, all these confiscated ships were laid up in Haifa harbour and eventually they became the first ships of the Israeli navy as soon as the mandate ended.

Then we went off to Greece, the King of Greece died and we were told prepare to mount a guard for the king’s funeral, thank heavens the commander-in-chief arrived in a cruiser because I was the gunnery office and my idea of how to conduct a funeral was to line the streets, it was strictly limited.

We had the summer travelling round the eastern Mediterranean, we went to Pola and Trieste, Trieste was under allied rule, Pola which is now Pula was given to the Yugoslavs and the Italians who lived there stripped their houses, everything down to the doors and windows and went back to Italy, this was all going on as resettlement after the war.

We came back to Malta in the Autumn, I actually did my guard duty there because the Duke of Gloucester came out to re-establish self government in Malta and open the Maltese parliament. We lined the streets, the soldiers with their rifles and I with my sword. But we weren’t allowed to do a sword salute because the street was too narrow and we were liable to hit the cheering Maltese so we just did a sort of neat salute.

At the end of the year went back to Palestine and there were two big ships the Pan Crescent and the Pan York which each took on about 4000 refugees in Romania, the Palestine government knew they were coming and they agreed with the Haganah that they would not resist if they were taken to Cyprus because they didn’t want any bloodshed.

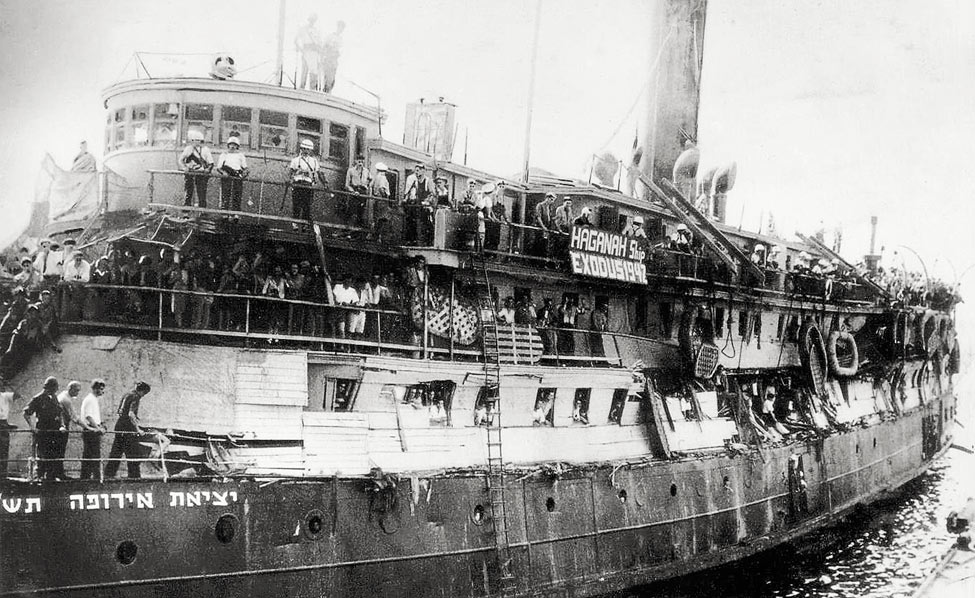

The one thing I’d forgotten was of course when the Exodus 1947 came in July they did put up resistance and it was the only time Jews were killed, but in that three years only 10 Jews were killed. When we went back for the 50th anniversary all the history professors in Haifa and Tel Aviv said thank heavens it wasn’t the Americans or the French or there would have been a lot more casualties because they were somewhat more brutal, we were very careful to avoid lives lost and there was no ill feeling towards these unfortunate refugees.

In August all the refugees offloaded from the Exodus 1947 were loaded on the three transport ships to be sent to sent to Cyprus but they wouldn’t disembark so they were sent back to Sète near Marseilles where they’d originated. The French refused to land them unless they were volunteers, none of them would agree to land except a few sick people and we were on patrol up and down just keeping an eye on these immigrant ships before we took them to Gibraltar when Bevin decided to send them all back to Hamburg, to the place where they had just risked their lives and survived. I think it was one of the things which swung the vote in November because they had such bad publicity for that action.

Fortunately we did nothing except just escort these ships and with great sympathy. So there we were at the end of the year we had the Pan Crescent and Pan York going into Cyprus and we saw them go in, meanwhile another ship slipped down the coast and landed in a hurry and got some people ashore because every now and then they did manage to outwit the patrols.

From there we sent down to Alexandria to escort the commander-in-chief on his farewell visit to Egypt and then down to Jeddah for a farewell visit to the king of Saudi Arabia. Jeddah had only taken the walls down a year or two before so all the sand blew in so it wasn’t a particularly attractive place.

We were loaded up with fireworks to put on a display, as gunnery officer I had to try and coordinate these fireworks which counter fired and eventually we had a magnificent explosion when most of them went of in one enormous sheet of fire. Didn’t do us any harm but must have looked quite impressive on shore. That was the furthest we went down into the Red Sea.

Then back we came again to Malta and finally in April we went back again to Palestine for our last patrol. As we came into Haifa we saw all the ships streaming out of harbour going up the coast to Lebanon because the Haganah had taken over Haifa. The British general said it’s part of the Jewish state, I’m not going to interfere, lets see what happens and the Haganah drove out the Arab resistance in no time. Of course all the Arabs were told to get out while the fighting went on and they’d be given the Jews houses when they won, but half the Arab population stayed and is still there, the rest became refugees and we saw then going up to Beirut.

We did one or two more interceptions at the end of April 1948 then Pal Yam decided it was a waste of time to send any more ships because in three weeks they could go into their own port.

We hung around off the coast, we were sent to stand by off Acre in case there was anything that needed doing but I think the Haganah took over Acre pretty easily and then we were sent to lie off Tel Aviv and Jaffa while the fighting went on with our guns pointing ashore. In practice I don’t think we’d have fired them because we couldn’t have told one side from the other or fired accurately, I think we‘d probably have fired into the sand if we had done anything, but it was rather alarming for me at the time as the gunnery officer to know what on earth we were going to do.

We came into Haifa for the last couple of days of the Mandate and the last morning I went ashore we went down to Atlit where the British army food depot was, to collect our rations and I went down with the trucks to see what happened and on the way back got off in Haifa and walked round the streets which were guarded by British troops and Haganah together at the barricades.

I went into the post office, which was full of people buying souvenir stamps, the British had withdrawn the Mandate stamps and the provisional government had overprinted all the charity stamps Doar, for postage, and put them on sale so they could keep the postal service going in the Jewish areas. I came out of the Post Office and saw the High Commissioner, who had flown out from Jerusalem, which was cut off so that he couldn’t safely come back by road. He had flown down to Haifa, got in a car and drove down to the docks where he went on-board the cruiser that was going to take him back to Malta and away.

Just a couple of hours before midnight all the British ships that were there left Haifa harbour, escorting out the departing High Commissioner with his flag flying at the mast of the cruiser. At midnight they crossed the three mile limit. The band on the aircraft carrier played God Save the Queen, the flag was lowered down and off he went into retirement.

We were dispatched to go down the coast to cover the British troops withdrawing to the canal zone, so the day after Independence we were patrolling down the coast, seeing the clouds of dust from the Egyptian forces as they moved up across the border. The British troops got back virtually unscathed. Egyptian spitfires then overflew us so we spread a Union Jack out on the deck, like during the Spanish civil war to show we were British. After 24 hours when the British troops got back safely they recalled us to Haifa and that was the end of our activities.

The Egyptians knew that there was a British enclave round Haifa going right down to Atlit, including an airfield at Ramit David and the Egyptians swooped down and attacked this airfield, which weren’t prepared for it and hit about half a dozen Spitfires. When they came back for the second strike, five or six Egyptian Spitfires were shot down by our planes and after that there was no more trouble.

RAF Spitfire in flames after attack by Egyptian air force on Ramit David airfileld, Israel 22 May 1948

Bevin had closed Haifa port so the Jews couldn’t get any more supplies in. This is something that rankled for a very long time. Haifa was kept closed until 30th June 1948 when the final British troops withdrew. They had been able to get some supplies, some small boats into Tel Aviv but it was a very deliberate British government act against the new state at the same time as they were letting the Arab Legion under General Glubb attack and take over part of Jerusalem.

Bevin had closed Haifa port so the Jews couldn’t get any more supplies in. This is something that rankled for a very long time. Haifa was kept closed until 30th June 1948 when the final British troops withdrew. They had been able to get some supplies, some small boats into Tel Aviv but it was a very deliberate British government act against the new state at the same time as they were letting the Arab Legion under General Glubb attack and take over part of Jerusalem.

My time was up in the Mediterranean and I went back to England. The Admiralty was asking people if they wanted to do various things, there was a list of interpreters wanted and for the first time modern Hebrew appeared, I slapped in to become an interpreter in Modern Hebrew, my captain recommended me and in September 1948 I was going to SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies) I was taught by a lovely man called Isidor Wartski who was the professor of Hebrew and by Ben Segal who was his assistant and later became the professor as well as a being a leading light in reform Judaism. I spent 18 month at SOAS learning Hebrew and getting married.

Then I was sent off to the Mediterranean again to be navigating officer of a tank landing ship which was doing a hush-hush job, in plain clothes, we didn’t have a uniform, we didn’t fly a flag. Surveying the south coast of Turkey at their request so that if the Russians invaded them we could get landing craft and our soldiers to their rescue as quickly as possible. That was rather fun for a couple of months.

Then we went to Malta, collected the commander-in-chief’s car and took it up to Anzio to land for the commander-in-chief to go and visit the Pope because it was holy year. We landed the car and had a chance to visit Rome for a day or two and then went back to Malta for a couple of months. I was sent to Israel, to the Hebrew university, because Professor Wartski had said “how can you expect him to be a good interpreter in Hebrew if he’s got no one to speak to in Hebrew?”

So they booked a room at the YMCA in Jerusalem, I was flown out and my wife was given the choice of going back to England or coming to Israel under her own steam, which she did. I was paid nine shillings extra a day to accommodate her, which certainly didn’t cover our costs, but she worked in the library at the YMCA, did her stint there, we were able to pay for our stay and had a very interesting time.

Due to the division of Jerusalem you had everybody living at the YMCA because the YWCA was in Jordan, the other side. We had Armenian monks, English bank managers, we had everybody under the sun staying there.

We also dealt with the British consul who was the other side in Jordan, through whom we got our post. We saw him once or twice and my wife invited his wife over for the day, because diplomats could get through. She came over the day that King Abdullah was assassinated, the border was shut and this poor woman was stranded in a foreign country, we lent her a toothbrush and a nightie and put her up for the night. The next day they opened the Mandelbaum gate for diplomats for an hour or two and she scuttled across back to Jordan, we never saw her again.

After the Hebrew University I transferred to an Ulpan which was much better, except that nearly all the candidates were Iraqi’s who spoke English. Somehow we all managed to learn Hebrew, then I was sent back to England and arrived just in time to see then end of the Festival of Britain.

This was now 1951. I was appointed first lieutenant of a frigate, HMS Plym, that was refitting at Chatham. I went to join her and discovered that something very special was going on. All sorts of equipment was being erected and there was a big hole cut in the bows. They’d taken the guns out and there was this place labelled WR which we knew couldn’t be the ward room down in the depths of the ship.

Eventually we discovered that we were going to take the first British atom bomb out to Australia.

When the refit was finished we went down to Sheerness and in a creek there a lighter came alongside. I, as the first lieutenant with a red and green flag, solemnly hoisted the first British atom bomb up from the lighter, lowered it down into the weapons room, hoping that I didn’t bang it against anything and blow us to smithereens. Of course we didn’t realise there was no primer in it and we were really quite safe.

So we then joined up with the aircraft carrier Campania that had on board the admiral who was in charge of the performance. We went round Africa, through Freetown, Simon’s Town, Mauritius and up to Freemantle, with everybody thinking we were escorting the Campania when in fact she was escorting us.

In Freemantle we had a couple of nice days seeing Perth, then we were sent up to Monte Bello which was a group of barren islands with no human life. Two landing craft that had been sent out and had laid the berth where we were to be secured for the final setting off of the bomb. All our sailors were gradually taken off and put on the Campania until there were nine of us left. All the ships had gone out in the lagoon, windward so we wouldn’t have anything blown back at us.

For the day of the practice, which happened to be Rosh Hashanah, I was left on board. All the other eight were evacuated, what I was supposed to do if anything went wrong I don’t know, so I sat on deck reading the New Year service to myself sitting on top of an atom bomb!

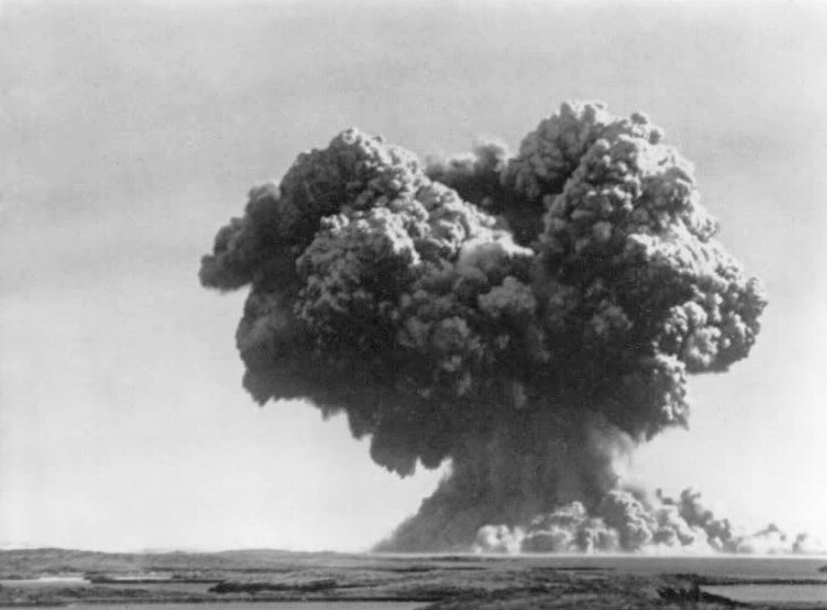

The next day they came back, we had supper and we were then evacuated to the Campania at about 0800 in the morning. Dr Penny who was the atomic bomb scientist had come out a few days earlier with the primer in his pocket, a few starter pistols and these turning handles for turning the thing live, he gave them out as souvenirs, I’ve still got one somewhere. He set it off with the usual mushroom cloud. We all had our backs to it, then we were allowed to turn round and saw the atomic cloud going up. Penny had been at the first American trial in the Pacific where they’d set up all this madly expensive equipment and the whole lot had been destroyed by the blast so Penny just put up lots of tar barrels, filled them with stones, weighed them down and got much better results as to what the effect was.

Oct. 3, 1952: ‘Operation Hurricane’ mushroom cloud rises above Trimouille in the Monte Bello Islands. Contained in the hull of the frigate HMS Plym and detonated almosty 3m below the surface of the sea, Britain’s 25kt explosion was of about the same size as Nagasaki.

Scientists went and did their bits of exploration and after a few weeks we were sent back to Freemantle. We were all accommodated on the Campania now and we went back to England in time for Christmas leave and that was that.

We had a big reserve fleet then and I was sent to one of the reserve fleet ships. We had the coronation review and we took all these ships out of reserve so as to produce a magnificent line of ships for the Queen to review for the coronation. There were a lot of active ships, but it was filled out with these ones from the reserve which were all sort of mothballed, the guns were all enclosed and so on, but it was quite fun.

The following year I was sent to join another cruiser, the Birmingham, going out to the far east, started at Chatham went out to Malta then the far east, on call in case Korea flared up. It was about a year after the Korean war ended but we were there to back up the fleet. We came back via South Africa and got home.

Then I joined naval intelligence division and was sent out to Singapore as the plans officer to the Malayan area where we organised the handing over of the Singapore navy, such as it was, to Malaya when they became independent. We discouraged independent Malaya from having expensive ships like cruisers, to start from the bottom up which I think they appreciated in the long run.

Went back to England and had two and a half years at Portland as the plans officer. Portland was where all the British navy ships had a month working up their new crews.

Finally I went out to Hong Kong as the first lieutenant of the naval base. where we maintained the ships of the far east fleet. I retired in 1966 with the rank of Lieutenant Commander, which is equivalent to Major, came back and joined AJEX.

Did you find your family was supportive of your naval career. Yes, my wife coped very well with the children while I was abroad on her own, she had her own family to help but it was quite tough

Do you share your experiences with your children and grandchildren, do they understand what you went through. I think up to a point, my second son was in the territorial SAS, so he’s very military minded and he’s been escorting me this last weekend (70th anniversary of VE day), we went to the cenotaph for the service and we went to Westminster abbey for the service representing AJEX and then did this march down Whitehall, that was fun, we met the prime minister and the first sea lord and various other VIP’s .

As you look back on your experiences and the part you’ve played in the world that we have, does the world today meet your expectations. I don’t know what I expected, its changed tremendously, I know when we were in Singapore we thought what a good opportunity for the children to meet other colours and races, nowadays you can do it all at home.

Follow reminiscences at Mike Stone, Reminiscences

If you enjoyed reading this, please help to share these stories with others and sign up for new work from Mike and Reminiscences here

Pingback: Britain’s Palestine Patrols | happygoldfish's jewish tv (and radio) guide